As late as the early 1990s, many Americans thought of going to see European films as desirably highbrow. European movies commanded 10% of the American box office. The problem with this was that European governments subsidized cinema, and the results were, well, uneven.

I recall going to see such a film titled “King Lear” as a university student only to be greeted by an old man sitting on a beach with the sounds of the waves coming ashore and (maybe?) someone whispering Shakespeare in the background. I decided that I had better ways to spend my cultural dollars, and so did many of my fellow Americans. European film viewership in the USA collapsed a few years later. Needless to say, there have been many fantastic European films, but the life lesson for me: never assume that the adjective European is a synonym for optimal.

All of which is prologue to the topic at hand, which is an opinion piece by Patrick T. Brown that effusively praises the European model of choice (whereby there is some but in which everyone must follow national academic standards and give national tests). Brown sums up his piece:

The parents’ rights and school choice movements aim to improve students’ academic, social and moral formation. That won’t automatically follow from a few policy wins. The new landscape for K-12 education will require the kind of studied, technocratic approach that doesn’t necessarily garner applause on a debate stage but is essential to making the permanent and lasting change conservatives would like to see.

A “studied, technocratic approach” is what we (allegedly) receive in American school districts. Democratically elected boards hire “expert” superintendents, principals and (usually) “certified” teachers. Sadly, we awake every day from our technocratic dream to a reality of widespread illiteracy, civic ignorance and philosopher-kings coronated by regulatory capture. If a “studied, technocratic approach” were the solution to our K-12 problems, we wouldn’t have them.

Over the years, school choice advocates have learned the hard way what not to do, or have we? Louisiana, for instance, enacted a heavily regulated school voucher program in 2008 that places onerous admission and curriculum restrictions on participating private schools, as well as a requirement to administer the state annual assessment. Accordingly, most of the state’s private schools chose not to participate, and many that did participate had falling enrollments before the advent of the program. When scholars published an academic evaluation of the Louisiana program, it was the first program to show negative results.

A basic flaw of technocracy is that the proponents imagine virtuous rule by disinterested philosopher-kings, but we wind up with politicized messes. For instance, we have witnessed a decline in the American charter school movement wherein incumbent operators team with charter opponents to throttle charter school growth. The proponents claimed that they were ensuring “quality,” but the correlation between technocracy and a vanishingly small number of charter seats is strong, quality non-existent.

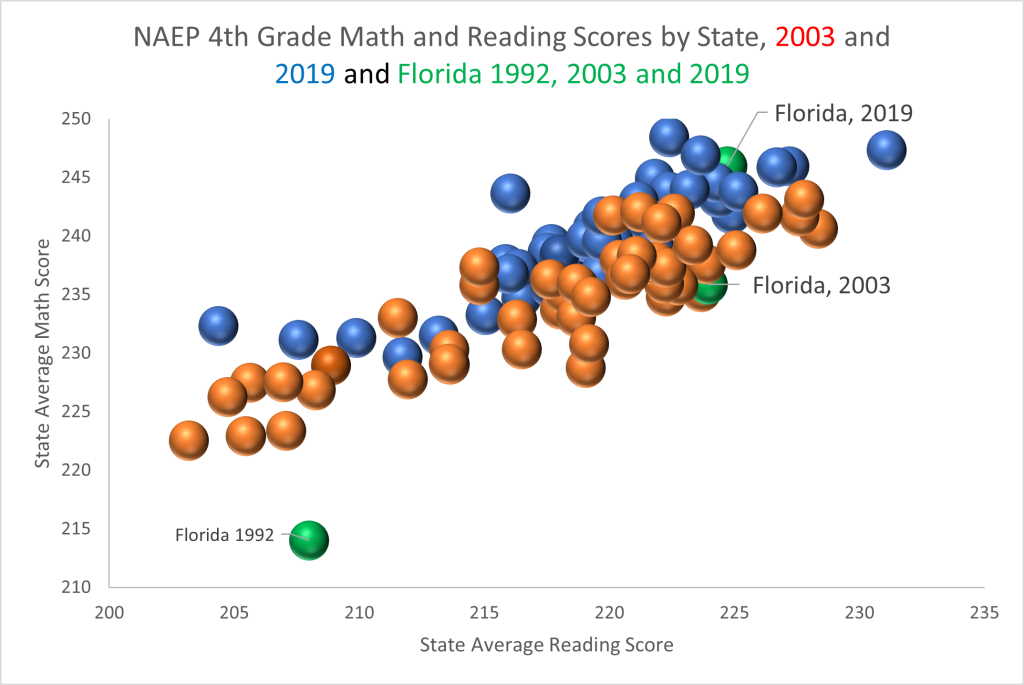

Finally, we have home-grown in the USA examples of choice programs delightfully free of European-style technocracy spurring broad academic improvement. Florida began private choice programs in 1999. Florida choice programs have a testing provision but allow schools to choose from a menu of assessments. This helps ensure a much higher private school participation rate than in Louisiana, which mandated the state test. It also ensures a greater diversity of schools.

Henry Ford once quipped that buyers could have a Model T in any color they liked, as long as it was black. Florida has had no need to offer assistance for families to choose any school they want, as long as they follow state academic standards and tests.

As Douglas Carswell (a wise European) wrote in The End of Politics “The elite gets things wrong because they endlessly seek to govern by design in a world that is best organized spontaneously from below. They constantly underrate the merits of spontaneous, organic arrangement, and fail to recognize that the best plan is often not to have one.” We should view European pluralism as an undesired floor rather than the highest possible ceiling.