The 74 recently ran an article titled Fewer Students, Crumbling Buildings: Columbus Looks to Shut Schools Again: Ohio district has tried to downsize, and failed, twice since 2016. But with 113 schools and just 45,000 students, officials have tough choices to make. The story notes a long-term trend toward enrollment loss in the Columbus, Ohio, district school system, and in particular casts an old, never renovated, and under-enrolled Columbus school called Como Elementary as a bit of a victim of a competitive Ohio K-12 environment. The article features another school called Hamilton that is two miles away. Should we however view Como Elementary’s reduced enrollment as a tragedy, or alternatively a triumph?

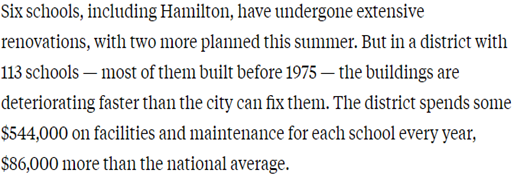

Como has a capacity of 400 students but sits at 243 students. Hamilton, which unlike Como has been renovated, has a capacity of 575 students but sits at 400.

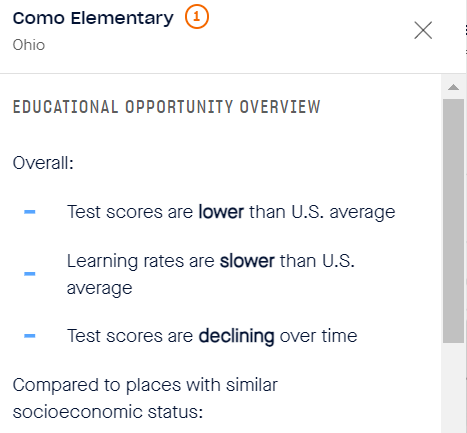

Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Project linked state testing data from across the country in grades three through eight, and currently for the years 2008-2019. If you were something like a charter school authorizer trying to decide whether to renew district schools, you would want to consider additional sources of information, but let’s start here. How well did Como Elementary perform in core tasks of teaching literacy and numeracy to students?

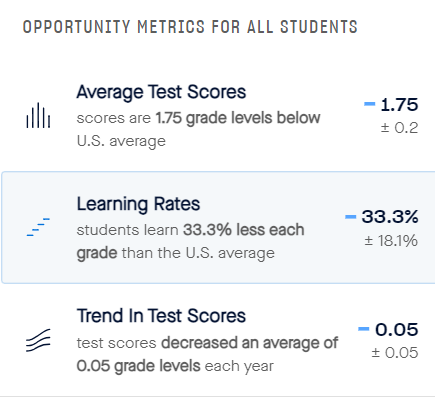

Lower scores, slower learning rates and test scores declining over time is not the hat-trick any school would want. The most problematic of all these statistics: a rate of academic growth that stood at 33% below the national average for the period covered:

Unfortunately, Como Elementary is not the Columbus school with the slowest rate of academic growth, and it has plenty of competition for the dubious “taught our students the least” crown. Now we get back to the facilities part of the story:

So right about now you might be thinking, rational human that you are dear reader, that the obvious solution here would be for the Columbus school board to close a number of underenrolled and low performing schools to right-size the districts. Drive more money into the classroom, that sort of thing. Hamilton for instance, just two miles away has space for 175 students, and an academic growth rate just 5% below the national average, not great but far better than Como.

Before you go thinking “this is EASY!” allow me to warn you that you are bringing your technocratic scimitar to a political gun fight.

School districts, while nominal democracies, have proven to be easy prey to regulatory capture by unionized employee interests. This is especially the case in large urban districts like Columbus. The main goal of unionized district employees is to preserve the jobs of their members, followed closely by increasing the number of jobs for their members. Closing district schools is not on the agenda. In addition, the general public tends to grab their pitchforks and torches on their way to school board meetings if when a district closes a school in their neighborhood, regardless of how many decades it spent miseducating students.

Oh course our dear friends in the K-12 traditionalist community would like to turn off all this nasty choice business so that Como Elementary can get the students and funding it needs to live happily ever after. A quick look at the Stanford data however reveals that Columbus charter schools are far more likely to have above average academic growth rates than the district schools. And oh, by the way, they are did it with far less funding per student.

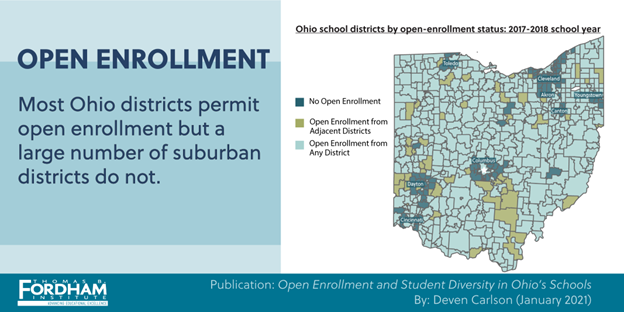

Given that Como Elementary taught their students at a rate 33% below the national average, I’m not inclined to think that it is a tragedy that they only have 243 students. It seems more like a tragedy for those 243 students to have to attend such a low performing school. Where do the seats lie for students attending such poor performing schools lie? In part, with the right mix of policies, out in the blue donut surrounding Columbus:

Unfortunately, Ohio legislators passed a private choice expansion last year that will offer the higher-income residents of those Columbus suburbs only a trifling amount of funding on a per pupil basis. I’m willing to wager that the vast majority of these folks will opt to remain with their gated community district schools, given that they are funded are funded as much as twenty times the rate as the choice program. This feature of Ohio’s voucher law is unintentionally denying opportunities to low-income urban students.

Ohio had been making some progress on addressing the problem illustrated so powerfully in the above map- removing geographic restrictions on charter schools for example. Hopefully they’ll rethink a feature of their voucher program that seems likely to cement economic segregation in schooling in place.

Don’t misinterpret any of this as “Como Elementary Delenda Est.” I have no idea how many district schools should operate in Columbus Ohio. I merely a preference for putting families in the driver’s seat of making the decision on which schools survive.