Over at Charter Folks, Jed Wallace weighed in on the recent Rotherham/Pillow/Yours Truly discussion on the state of the charter school movement in an era of increased popularity of ESAs.

Wallace seconds Travis Pillow’s observation that both ESAs and charter schools are simultaneously flourishing in Florida, and notes that it is also happening in states such as Iowa. Wallace then posits that the attraction held by Republican lawmakers for ESAs may prove fleeting:

Because, as we all know, universal ESAs and vouchers have got issues, and we’re just starting to see policy makers begin to grapple with them.

Top of mind is how to pay for them.

In Arizona this month, we saw the state approve a budget …that cut 3.5% from all other agencies and delayed a $333 million dollar contribution to a water infrastructure account in order to afford its universal ESA program, which has become a new $429 million line item.

Arizona’s budget is widely discussed, but the reality is that this narrative has little to do with reality. In reality, Arizona’s ESA program is a part of the Arizona Department of Education’s budget, and that budget had a $28 million surplus last year. To paraphrase the bard, Arizona’s budget had 99 problems last year, but ESA a’int one.

A bit later in the piece Wallace took issue with your humble author’s contention that the charter school movement suffers from a Baptist and Bootlegger problem:

While I’m all in with Matt on our Baptist problem, the fact is I just don’t see much evidence of Bootlegger complicity.

Yes, stifling regulation and general blowback is a massive problem in the charter school space, all the more so now that private school options can expand at will in many parts of the country. And yes, massive compliance challenges are particularly daunting for smaller organizations to contend with. Many are getting crowded out altogether.

But are big CMOs actually okay with, or in some way are supportive of, the heaping on of additional regulation that is happening in CharterLand these days?

All to squeeze out competition coming from “moms and pops?”

Not from where I stand, at least.

CMOs are as frustrated by debilitating new regulation as any category of charter school organization.

Examining the handy-dandy charter school ranking document from the Center for Education Reform, I count seven state charter laws that passed since 2010: Mississippi (2010), Maine (2011) , Washington (2012), Alabama (2015), Kentucky (2017), West Virginia (2019) and Montana (2023).

The number of charter schools operating in these states as of April 2024: Mississippi 10; Maine 9; Washington 18, Alabama 14, Kentucky 0; West Virginia 24; Montana 1. Obviously, it is too early to draw much in the way of conclusions from Montana’s law operating for a single year. I would also entertain the notion that 24 schools in five years given West Virginia’s modest population might be considered not bad.

Overall, however, the math proves unforgiving: collectively these states have had 61 years of charter school laws but have produced 76 charter schools- an average of a net increase in charter schools of 1.24 per year across seven states.

Combined these states have well over 2 million more residents than Florida. Since 2011, however, Florida managed to average a net increase of 18.8 charter schools per year.

Now let’s see how the national charter school groups rank these seven laws, starting with the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. The most recent ranking, from 2022, came before the passage of the Montana law. The National Alliance initially ranked the Kentucky law 10th but excluded it after — cough — it produced zero charter schools.

A few observations: Alabama’s law ranks above Florida’s, despite 707 charter schools operating in Florida compared with 14 in Alabama. Florida’s charter school movement might wonder just what exactly is so special about that Alabama charter law. Next, West Virginia has only 9% of the population of these five states and over a third of the charter schools but the lowest ranked law. Alabama, Washington, Mississippi and Maine have 48 years of charter schooling collectively, whereas West Virginia has only five. The West Virginia law however ranks 28th, whereas those other four states rank third, sixth, seventh and 10th respectively.

The National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) apparently exited the charter school law ranking business after 2015, best I can discern. That 2015 publication, however, has plenty of gems to admire: for instance. Alabama’s law ranked fourth, with NACSA approvingly noting “Alabama passed a new charter law in 2015 that is based on best practices in charter school policy.” The publication ranked Mississippi’s law as tied for sixth place, again noting, “Mississippi passed a new charter law in 2013 that is based on best practices in charter school policy.” “Best practices” did not seem to include opening many actual charter schools.

Delightfully, however, the Center for Education Reform gives West Virginia the highest ranking of any of the states passing laws since 2010 with a “B” grade. Montana and Alabama received a “C;” Mississippi, Kentucky, Maine and Washington each received a “D.”

Summing up, the National Alliance ranks charter laws according to adherence with a model bill that seems to have a very strong track record of not producing many charter schools. NACSA meanwhile described non-productive state charter laws as reflecting “best practices.” Charter schools clearly have a “Baptist” problem, and more recently practical challenges such as higher interest rates. We are dealing with a complicated reality with multiple factors at play.

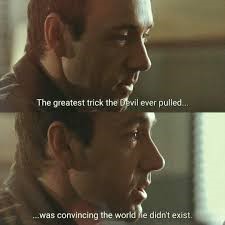

Jed does not want to believe in the Bootleggers. The Bootleggers, however, believe in passing as many weak charter laws as possible and then singing their praises. They have enjoyed a great deal of success since 2010.