Education Next published a piece recently by Holly Korbey called The Tutoring Revolution, which reads in part:

Recent research suggests that the number of students seeking help with academics is growing, and that over the last couple of decades, more families have been turning to tutoring for that help. Private tutoring for K–12 students has seen explosive growth both nationally and around the globe. Between 1997 and 2022, the number of in-person, private tutoring centers across the United States more than tripled, concentrated mostly in high-income areas like Brentwood. Many students are also logging onto laptops to get personalized digital tutoring, with companies like WyzAnt and Outschool reporting they’ve enrolled millions of students for millions of hours in private, video-based learning sessions that students access conveniently from home. Market reports estimate the digital tutoring market was worth $7.7 billion globally in 2022, with projections of a compound annual growth rate of nearly 15 percent from 2023 to 2030.

Recall as well one of the most fascinating parts of Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast series wherein Lacey Robinson, a veteran teacher in inner-city public schools described taking a teaching position in the suburbs. Robinson wanted to learn what the suburban schools were doing to teach literacy to upper-income students, and then bring it back to the inner-city schools. She discovered that the suburban schools were providing their students with approximately nothing:

“They were learning to decode at home with tutors. I know, because I became one of them.”

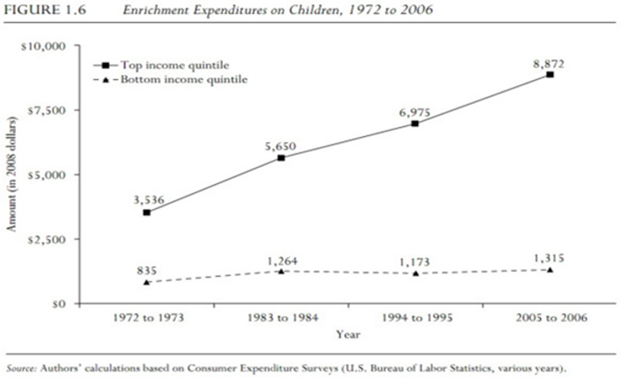

If you speak with or poll American suburbanites, they have traditionally expressed a fair degree of confidence in their public schools, which they tended to describe as either “okay” or “good.” Monitor their actions over time, however, and you see that they placed a greater and greater reliance upon tutoring. Most were enrolling their children in public schools, but they were relying upon them less and less and upon tutoring and other private enrichment spending more and more.

In 2015 Wired ran an article called The Techies Who Are Hacking Education by Homeschooling Their Kids. The unstated background message of this article: Silicon Valley families had decided that the time opportunity cost of enrolling their children in a school, even a public school they had already paid for with their taxes, was too high. Key quote:

“There is a way of thinking within the tech and startup community where you look at the world and go, ‘Is the way we do things now really the best way to do it?’” de Pedro says. “If you look at schools with this mentality, really the only possible conclusion is ‘Heck, I could do this better myself out of my garage!’”

Your garage, and perhaps your local Kumon, museums and hackerspaces. Early during the pandemic, Silicon Valley families created a Facebook group called “Pandemic Pods” with spontaneous order scratch to a very itchy group of American families.

The COVID-19 pandemic opened the eyes of many families regarding how much responsibility they should take for the education of their children: all of it. The public school system operates in the interests of its major shareholders (i.e., those deciding school board elections). Broadly speaking, mere taxpayers and families don’t qualify. One can describe the public school system as broken, but you can more precisely observe that it is operating as intended.

If you doubt that last statement, I invite you to attempt to lobby for a meaningful change in the way the public school system operates. You’ll meet all kinds of interesting people. Sadly, most of them will be eager to die on a hill defending the K-12 status quo.

If someone purposely designed an education system to generate inequality, they would have some difficulty exceeding the ZIP code assignment plus tutoring for those who can afford it status quo. The question moving forward is not whether we are going to have more a la carte multi-vendor education. The question is what, if anything, we are willing and able to do to distribute that opportunity.