Florida's public schools score among the best in the nation in nine-year-olds' reading achievement. For low-income students, their results are the best in the nation, period.

And they also deliver for taxpayers, producing these results at some of the lowest costs in the country.

Those key head-turning points from a new analysis published by the American Enterprise Institute.

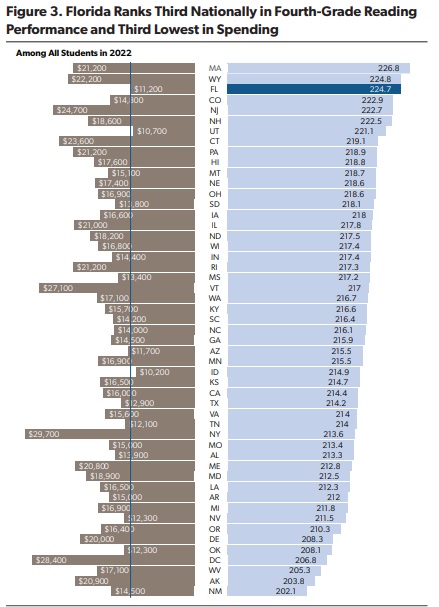

This chart tells the tale:

Florida's public schools spend less than most other states but produce stronger fourth-grade reading achievement. Source: AEI

The analysis, by Kathryn Perkins of the Florida Charter School Institute, Paul Powell of True North Classical Academies, and Jeff Wasbes of DynEval Solutions, looks at fourth grade reading results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. It shows Florida's already-impressive national standing improved after the COVID-19 pandemic, when achievement slid backward in most states but held steady in Florida.

The usual caveats apply. The national assessments are high-quality and well-administered, but they are only taken by a sample of students in each state. As a result, stack-ranking states can obscure the fact that students in many states may have statistically indistinguishable scores. The analysis focuses on fourth-grade reading, a subject where Florida has historically excelled. Its results in fourth-grade math and eighth-grade reading aren't as strong.

The NAEP results also can't tell us which policies or classroom practices drive Florida's impressive performance.

On the policy front, some advocates might point to Florida’s large Voluntary Prekindergarten program, which may give students an early reading boost that fades as students get older.

Others might point to Florida’s school accountability approach, which rewards schools that prioritize the lowest-scoring students.

Or the growth of charter schools and scholarship programs, which now help more than 1 million Florida students find learning options that work for them, and, at the same time, help drive improvements in surrounding public schools.

Or the state’s major investment in ensuring all schools deliver high-quality, research-based reading instruction, begun under Gov. Jeb Bush and continued since.

The results might also reflect Gov. Ron DeSantis’s decision to reopen school campuses earlier than his counterparts in many other states, which could have stemmed the tide of learning loss in early literacy.

More research should try to tease out these nuances, but until that happens, a reasonable hypothesis is that all of these factors play a role in our state’s remarkable progress over two and half decades.

I was a Florida elementary school student when our state’s bottom-of-the-barrel performance was constant front-page news. The good news about our state's national leadership in reading outcomes, on the other hand, continues to sneak below the radar.