In the film “The Blues Brothers,” Jake and Elwood Blues impersonate a country-western band to get a gig at Bob’s Country Bunker, hoping to score some quick cash to help fulfill their “mission from Gawd.”

In the film “The Blues Brothers,” Jake and Elwood Blues impersonate a country-western band to get a gig at Bob’s Country Bunker, hoping to score some quick cash to help fulfill their “mission from Gawd.”

Performing on a stage rimmed with chicken wire, the band’s initial rhythm and blues set is met with a cascade of boos and hurled beer bottles. The stage lights go out, prompting the band to wonder what’s going on. One member speculates, optimistically, that a fuse blew. “I don’t think so, man,” says Blue Lou, the saxophone player. “Those lights are off on purpose!”

It’s important to understand that the level of economic and racial segregation in district schools isn’t accidental, either. A recent New York Times column referencing a 2003 proposal to decrease this type of segregation has become part of the 2020 presidential race conversation.

In “When Elizabeth Warren agreed with Betsy DeVos: How a heterodox professor became a predictable candidate,” David Brooks quotes from a book co-authored by then professor Elizabeth Warren, “The Two Income Trap.” Brooks laments the loss of a heterodox public intellectual who morphed into a predictably doctrinaire presidential candidate, writing:

Many women entered the labor force to give their family more financial security. But an ironic thing happened. All the new dual-income families started bidding up the price of housing in neighborhoods with good schools. They started bidding up the price of day care and college tuition. Two-income families found they had less economic security, not more. “Even as millions of mothers marched into the work force, savings declined,” Warren and Tyagi wrote. This is the two-income trap. And the results were especially devastating for single-income families and single mothers who had to compete in the hyped-up, dual-earner world.

Warren did not argue that women should leave the labor force. Instead, she favored helping parents by providing them with school vouchers and school choice. “Fully funded vouchers would relieve parents from the terrible choice of leaving their kids in lousy schools or bankrupting themselves to escape those schools,” Warren and Tyagi wrote.

“An all-voucher system would be a shock to the educational system, but the shakeout might be just what the system needs,” they continued. This is exactly the argument that Education Secretary Betsy DeVos uses to support school choice.

Sen. Warren’s presidential campaign website endeavors to stress that Warren’s book did not support private school vouchers. Dusting off my copy of the book, I found this claim to be correct. Although Professor Warren used the term “voucher,” what she called for was basically the equivalent of an open enrollment system:

Short of buying a new home, parents currently have only one way to escape a failing public school: Send the kids to private school. But there is another alternative, one that would keep much-needed tax dollars inside the public-school system while still reaping the advantages offered by a voucher program. Local governments could enact meaningful reform by enabling parents to choose from among all the public schools in a locale, with no presumptive assignment based on neighborhood.

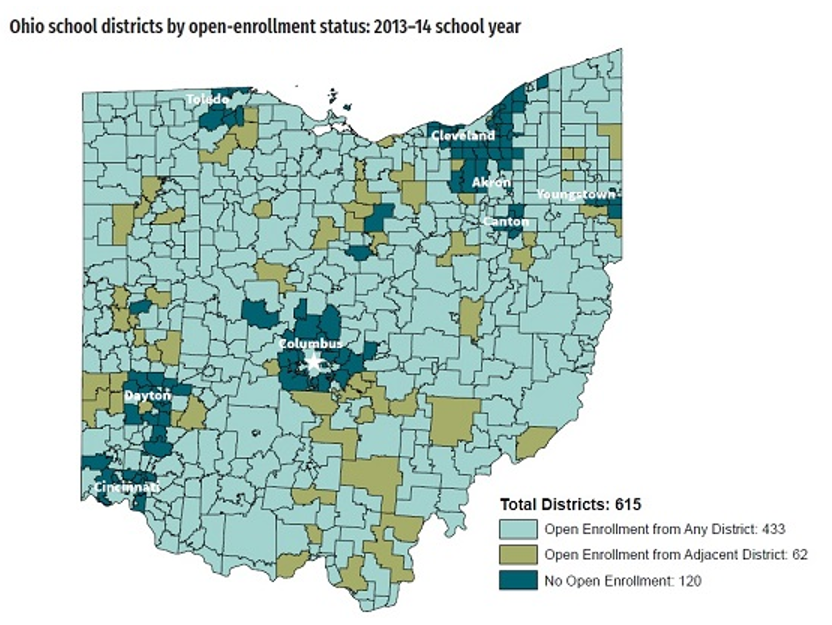

I’m a big supporter of open enrollment, and it is tragically understudied. What we do know, however, is that it is far more complex than simply passing an open enrollment law to get open enrollment transfers to happen. For instance, a decade after Professor Warren’s proposal, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute found open enrollment in Ohio looks like this:

This map shows every major urban center surrounded by districts not participating in open enrollment. The Columbus area, for instance, looks like a non-participating donut, followed out a bit further by some green districts. They participate, but only with adjacent districts. Who do you think those districts might be trying to avoid?

I fear Ohio is not much different than the typical case.

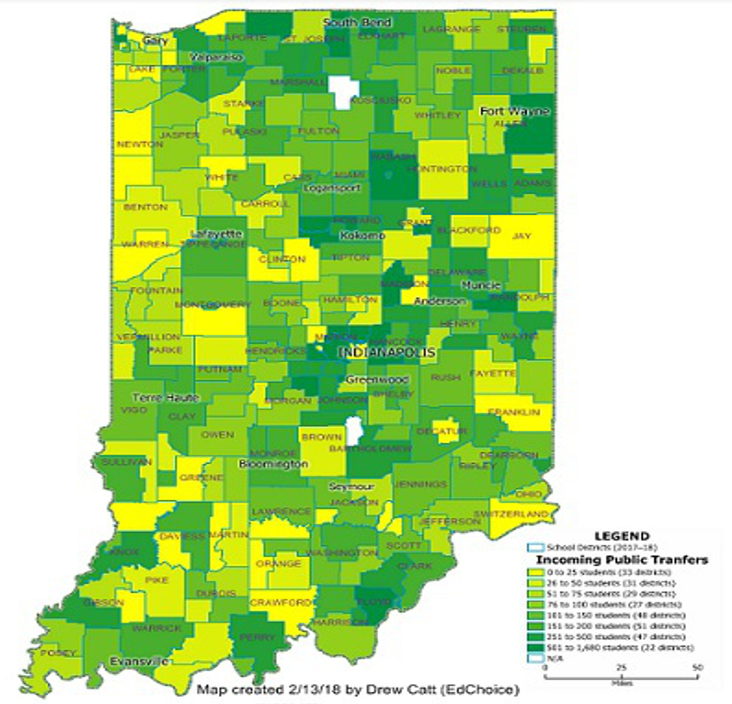

EdChoice created a similar open enrollment participation map for Indiana. Here we see a once-frozen system starting to thaw.

Changes to Indiana’s funding formula helped create momentum for families crossing district boundaries. The details of funding formulas as well as the breadth of choice programs can influence the amount of open enrollment. Indiana’s private choice programs have been geographically inclusive, and this is a move that Ohio will emulate after the 2019 legislative session. Hopefully, the move will help open Ohio suburban districts to transfers.

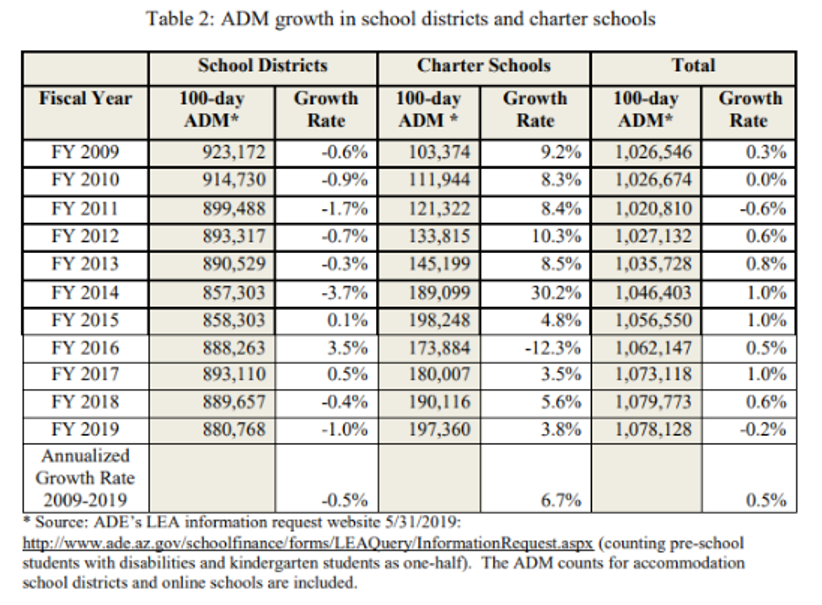

Meanwhile, the enrollment trends in Arizona essentially have all districts participating in open enrollment. Arizona charter schools operate across community types in Arizona, and their growth since 2009 has created an incentive for districts to participate.

Legally, Arizona districts can choose not to participate in open enrollment, but with the supply of school seats increasing, this choice is not practical. Arizona charters created an incentive for some districts to participate in open enrollment. With increasing numbers of charter schools and a growing number of districts participating, it became impractical not to participate.

Open enrollment students currently outnumber charter school students nearly two to one in the Phoenix area, and Arizona is one of only two states that have made statistically significant gains on all NAEP exams since 2009.

Elizabeth Warren’s heart was in the right place, and open enrollment is vitally important. As a practical matter, however, some important details like funding formulas and some tension in the system in the form of choice options are needed to make her view a reality.